The days between the development building phase and prototype presentations on April 22nd were absolutely crazy. The four project teams had a mere two weeks to design, build, and prototype their initial project ideas around themes of inclusion that could be incorporated into their local communities. All of the teams worked hard to solidify their ideas and used rapid prototyping to mock up something tangible for their presentation pitches.

The pitch structure took inspiration from Silicon Valley, and gave each group a chance to show off their work using art as a tool to engage users in thinking about ways their prototype could make a difference in their community. It also motivated them to move their ideas forward while making the right connections along the way.

The day started with Marina introducing Garage’s partnership with ZERO1 and their focus on the topic of inclusion for their spring programming. I introduced the American Arts Incubator workshop and gave an overview of the topics around inclusion we had discussed as a group, the field trips we went on, and our interviews with people with disabilities over the past three weeks. After congratulating the teams on all the hard work spent on their initial prototypes, we kicked off the event with a series of pitches by the teams which included time for feedback, discussions, and Q&A from the audience.

It was important for teams to present a tangible prototype along with their pitches to help the audience connect to their ideas and messages. It helped bring them into the reality that each team was trying to create: a vision of a future world where inclusion is tackled by technology, second-nature apps, customizability, and unique fashion tastes.

At the heart of each project was a message for the general public to start actively addressing inclusion in the community — through education, breaking stereotypes, instilling healthy public perceptions, and co-creating opportunities of inclusive collaborative play. As each team worked to solidify these themes, they had to find opportunities in design, whether their message was a call for more inclusive museums or normalizing communication through emotions. It was important to emphasize the prototyping process in the weeks leading up to the exhibition.

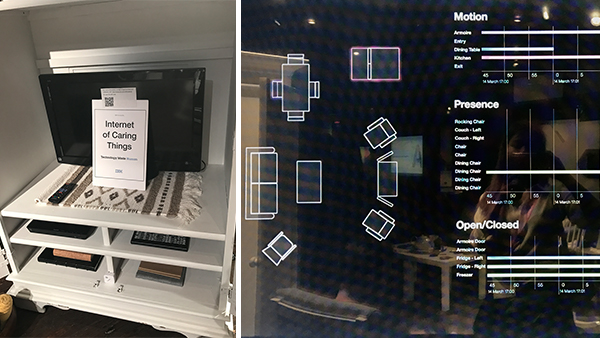

The day ended with a round table, trade show-style setup. I was inspired by my experience at SXSW where finalists had their prototypes out by their booths for demos and conversations. In the space we had at Garage’s Educational Center, we set each of the prototypes along the walls. As the presentations ended, the audience was invited to move around the room to each table and interact with the prototypes and ask the group any further questions. This allowed for more casual and candid conversations among well-connected artists in the theater scene, the art and gallery spaces, and those from the disabled communities working between art and inclusion.

It was great to see the excitement that ran through the whole room and the genuine curiosity everyone had for how technology could be integrated with both art and social inclusion. It advanced the topic of inclusion into the realms of designing services, apps, and products that could one day inspire ways to address inclusion all over the world.

Sensory Light Spaces Installation

by Elaine Cheung

In addition to the four community projects, I created a project that I did research for on the ground in Moscow and in America before I left in April. Garage MCA’s Department of Inclusion had been interested in adding future sensory rooms and universal playgrounds to their future expansion efforts at the museum.

Sensory rooms are generally used in hospitals or schools where kids on the autism spectrum can explore their tactile senses in a safe setting, as opposed to the often overly stimulating environments of our cities which can lead them to sensory overload. Sensory rooms are meant to be mentally calming spaces to help facilitate learning and play. In approaching the concept of a sensory room as a designer and artist, I questioned how this kind of room could be designed in our smart technology era.

Technology enables people with disabilities more freedom and independence due to the adaptability and computing power of smaller devices like phones and microcontrollers. The next step would be to think beyond adaptive technology and consider the design of experiences and environments for those with disabilities. What if our environments were able to pick up emotions and calm us down in ways that delight and move our senses?

With the therapeutic aspects of sensory rooms, I created my own version that aims to visualize ways in which environments can be more friendly and responsive to the needs of someone with a disability — allowing for interaction in an environment where they can play and learn simultaneously. The installation broaches ways of creating alternative healing experiences with technology and attempts to view disability through the lens of play, access, and sensory creativity.

When people sat on the pillows, low and relaxed chords would play as the other pillows joined in unison. The LED lights on the wall mimicked the effect of water bubbles in the Sensorium room. But instead of using water and light, the animation of the LED strips flowing up and down at a slow and steady pulse created a calming effect with purely digital outputs. To further encourage social play, proximity sensors were installed so that when viewers moved around, they could change the hues of the light. The installation was placed alongside the other four community projects and it was exciting to watch as participants engaged with the work.

I was really excited by all the enthusiasm participants had for the subject of inclusion in art and for speculative design thinking, even at the level of looking at how sensor and DIY electronics technology can impact the lives of people living with disabilities. The Incubator brought people from different backgrounds that have the same commitment to creating inclusive experiences. It would be inspiring to see American museums consider disability and inclusion in their future programming and exhibitions. Here in Russia, participating artists displayed grace, commitment, and passion to building communities and creative experiences accessible to truly anyone.

Exhibition on April 22, 2017

Official Event Postings:

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art’s Website