Since January 2017, I have been attempting to become a human version of Amazon Alexa, a voice-activated AI system for people in their own homes. The project is called LAUREN. Anyone can visit get-lauren.com to sign up.

The process begins with an installation of a series of custom-networked devices that include cameras, microphones, switches, door locks, faucets, and other electronics. For three days, I remotely watch over the person 24/7 and control all aspects of their home. I attempt to be better than an AI, because I can understand them as a person and anticipate their needs.

LAUREN Testimonials, 2017. Directed by David Leonard.

This project represents one of the main themes of my practice, examining social relationships in the midst of surveillance, automation, and algorithmic living. In particular this past year, I’ve been focused on the concept of “home.” How do we know when we’re home, and how does technology fit into this feeling?

I’ve been investigating these questions through a series of projects. In 24h HOST, visitors take part in a small living room party that lasts for 24 hours, driven by artificial intelligence that automates the event and is embodied in a human HOST. Prior to the performance, guests register to attend via a website. Their online social identity is scraped and analyzed, and they are assigned an optimal time at which to arrive. Every five minutes throughout the party’s duration, one guest departs and a new guest arrives. I am the host.

Lauren McCarthy, 24h HOST, 2017. Photo by Boudewijn Bollmann.

In The Changing Room, a custom software installation space invites participants to browse and select one of hundreds of emotions, then evoking that emotion in them and everyone in the space through a layered environment of light, visuals, sound, text, and interaction exhibited over the entire space. While it imagines a smart environment that controls feelings, the piece simultaneously invades and cares for the emotions of passersby.

Lauren McCarthy, The Changing Room, 2016. Photo by Kyle McDonald.

We are meant to think smart home devices are about utility, but the space they invade is personal. The home is the place where we are first watched over, first socialized, first cared for. How does it feel to have this role assumed by artificial intelligence? Our home is the first site of cultural education; it’s where we learn to be a person. By allowing these devices in, we outsource the formation of our identity to a virtual assistant whose values are programmed by a small, homogenous group of developers.

I’m looking forward to bringing these research themes to Gwangju, South Korea next month as part of the American Arts Incubator. Working with a group of twenty local participants, we will tackle the issue of social inclusion. Nearly 96% of South Koreans identify as ethnically Korean, which provides a unique challenge to addressing inclusion, and is just one challenge in the broader picture of diversity. Other aspects we will consider include disability, gender roles, and identity in the context of the May 18 1980 Democratic Uprising that began in Gwangju.

It’s obviously tricky to come into a place as a visitor and try to talk about social inclusion and identity. So I am planning to do a lot of listening and learning. As a starting point, we will use the concept of “home.” Home is an idea we can all relate to—we have all felt at home at some point, whether it is a physical place, a group of people, or a mode of being. But what makes someone feel “at home” and what does it mean to belong in a space, community, or city? What might a future home look like, if we imagine one that is more inclusive?

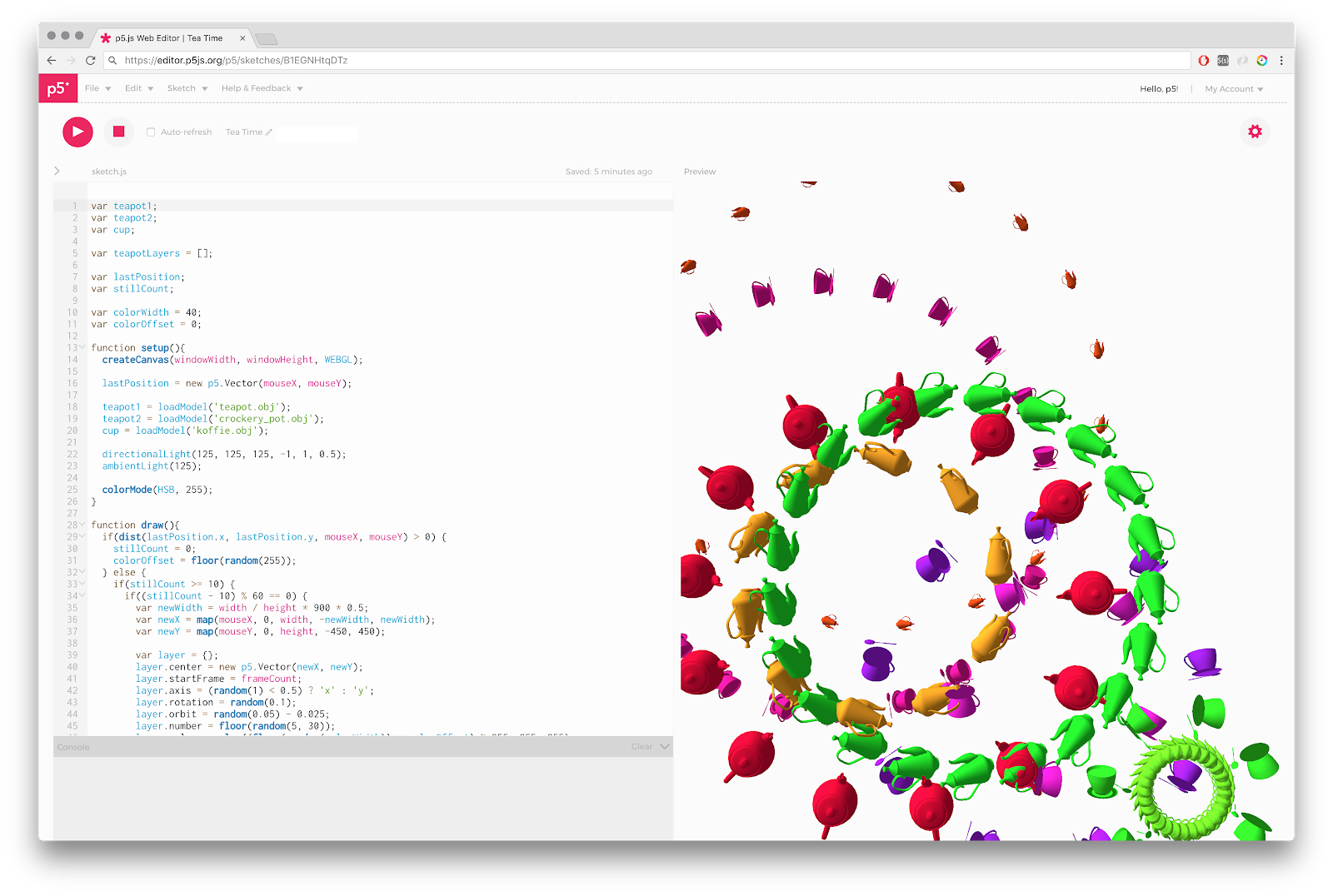

We will create an interactive installation driven by machine learning that represents our group vision of a future smart home. Rather than imposing values and protocols, this home will aim to create inclusive spaces for open conversation and freedom of expression. We will also visit some “homes” around the city of Gwangju, and challenge our ideas of what form and place home needs to occupy. To build the installation, we’ll be using a tool called p5.js, which is designed to “sketch with code” and learn coding through making art.

p5.js Web Editor. Photo by Lauren McCarthy.

For this month-long project, I’m partnering with the Gwangju Cultural Foundation. They are an organization that is very tied into the local culture and arts, and they’ve been extremely helpful as we prepare for the workshop and incubator.

Gwangju Cultural Foundation workshop space. Photo courtesy of Gwangju Cultural Foundation.

I’m looking forward to getting on the ground and learning all I can. If you’d like to follow along, you can join our Facebook group. We’ll have an open house at the end of the exchange, where the final installation and team projects will be on display from May 10-11, 2019.