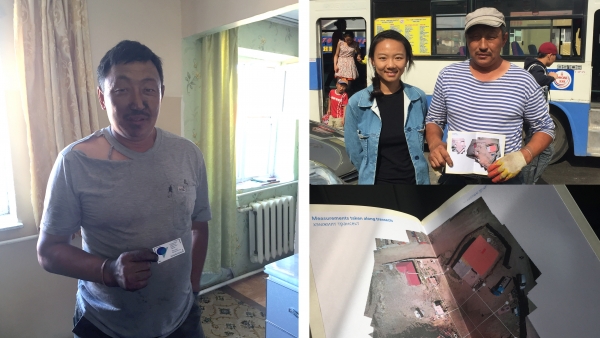

By the end of my trip in Ulaanbaatar, the weather changed from steady rain to an intense, dry heat. Throughout this experience, I had an amazing group of 4H volunteers along with Binderya (my superstar project assistant) surveying ger district residents for the Nomadic Mapping Collective. Long days of sun and hot weather were no deterrent, and many of the ger district residents offered tea, candy, and respite. It was the complete opposite of a visit from Comcast, and it took me awhile to adjust to this overwhelming hospitality from the residents. I originally imagined a string of visits in one day, showing up to a hasha (the household yard), going through all the measurements, and leaving. This vision of “get-it-done” home visits did not come to fruition, yet the reality became a welcome detour — I learned a lot from talking with the members of each household. By the end, we started shortening the name of the Nomadic Mapping Collective to just “Mapping Collective” — the nomadic part was blatently obvious to all involved.

Our collective led a user-centered design process that I never had imagined we could accomplish (language barrier being one obstacle!). Over 100 interviews and paper surveys were gathered from three distinct districts in Ulaanbaatar — Songino Khairkhan (one of the poorest ger districts by income level), Chingeltei, and Sukhbaatar (one of the older, most established ger districts).

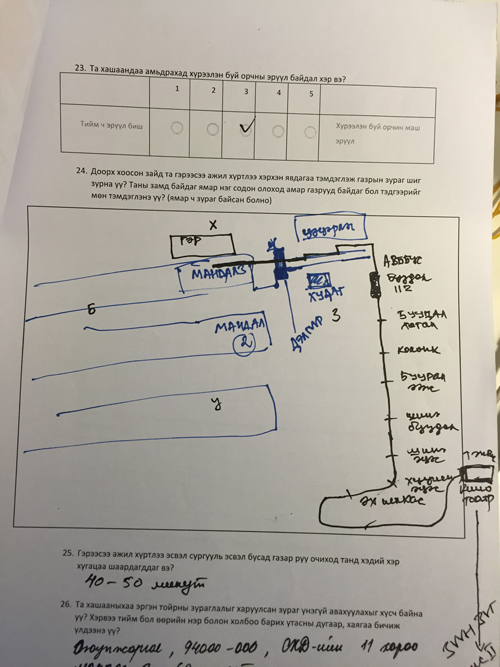

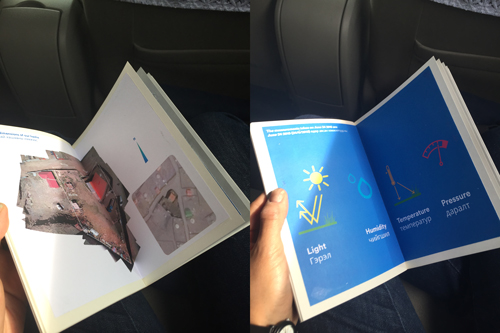

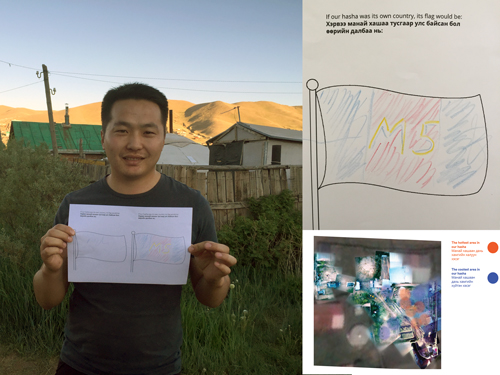

We ended up doing detailed site surveys of 15 hashas, or yards, and making these into artist edition booklets. These artist edition booklets were a collaborative effort by the Mapping Collective and the members of each household we surveyed, and were given to each hasha household for them to keep. It wasn’t an official legal document (although I did try to convince Binderya that a public notary should stamp our editions — she insisted that it would have been near impossible), which is why we referred to it as an artist edition. Still, these printed documents were a way to empower residents with actionable data for designing their yards, and to allow ownership of their own data.

We were tackling two issues with our artist editions — (1) the misconception that ger districts, as informal spaces, were full of shoddy, haphazard, non-data driven planning / construction by residents, and (2) the common practice of ger district data being collected by many government organizations, foreign aid orgs, and other NGOs but not shared with the residents being surveyed. From the beginning, this lack of data accessibility was a sore point amongst many ger residents. Being excluded from the data led many residents to be suspicious of the data collection processes, and limited the number of residents willing to participate. Instead of being privy to the survey results and thus empowered to change their environments based on the data, residents watched data flow to “outsiders” who designed and planned the ger districts. The Mapping Collective’s artist edition sought to change this by collecting and sharing actionable data that supported residents to make decisions (e.g., where best to put a small garden or a greenhouse). Also, we hope these artist editions will be considered under intellectual property law, and that the data will hold legal gravity as a work by the hasha residents that could not be taken or copied without their permission.

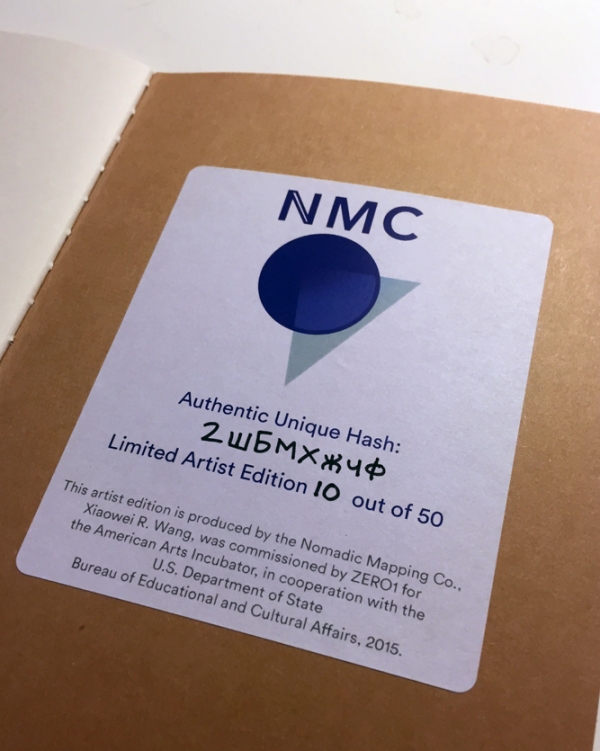

Referencing legal / contractual art such as the work of Superflex (http://superflex.net/tools), when a resident agreeds to have his/her hasha surveyed, the resident becomes part of the Mapping Collective. Because the Mapping Collective owns the intellectual property of each artist edition, the resident thereby becomes “owner” of this artistic representation of real data.

We built into this artist edition analysis of the hasha characteristics like hottest place, coldest place, most humid place, best places for planting, etc. By including this analysis, we transformed the idea of data-driven design in informal settlements into reality. Many of the residents expressed interest and excitement in interviews and paper surveys about improving their hashas — which proved right our hypothesis that ideas of “run down ger districts where no one cares about their environments” were simply a false construct. Most of our survey respondents chose to live in ger districts because it offered them the open space to have at least some sort of nature or connection to the landscape in a way that apartment house living did not.

Finally each artist edition was given a special hashid in Cyrillic as a mark of authenticity — there now exists a list of official, Mapping Collective-recognized hashids.

This unique hashid provides access to each hasha owner’s data online, in a private way, almost like a data locker. Residents will be able to access their data via nomadicmapping.org by entering their hashid (which was done in Cyrillic, to accomodate Cyrillic keyboards). Having some data online made sense, as there were a lot of measurements, calculations, and analysis that went into each hasha — we couldn’t fit all of the data into one printed booklet!

When I began this project, I thought that the Mapping Collective could corral the data simply through open-source collection methods. Yet through extensive surveys and face-to-face conversations, it became clear that data ownership and control over channels of distribution were extremely important in Ulaanbaatar, almost culturally antithetical to certain Californian ideals of open sourcing everything.

As we discussed this project with participants, a lot of them actually brought up the incident of Google Maps in Japan, where privacy was a major concern (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Street_View_privacy_concerns). It was here that I learned a lesson: while in certain pockets of the West we love and exoticize open data and public data, it’s not true everywhere. In fact, in at least half the world, the idea of putting all your home’s data online is a violation in so many ways – why do it? One resident even brought up the weirdness of Google Maps and that maybe the idea of “public” data was just a ploy for Google to gather information about people without seeming too sinister. This expressed need from residents to keep their data private and truly have ownership of it reaffirmed our format for the artist editions, and emphasized the Mapping Collective’s belief in empowering the ger district residents through actionable data.

Meanwhile, while conducting ger district surveys, we also were organizing the final community event, to be held at a beautiful Ulaanbaatar park. All four projects had either begun or were nearing completion.

The Art Boortsog team (http://youtu.be/PsOS2QtWx7k ) had been going out every day, to some incredible places in Ulaanbaatar that no one would think to go — everywhere from ger districts to sites of extreme poverty. For project creators Ganzug and Enerel, it was an up and down that brought some invaluable food for mind and body to marginalized communities, but also made them confront aspects of their practice in new ways. During the final event at UB Park, they showed images from their project and made Boortsog.

Our Street is Our Home created a set of gates for their installation at the final event — bringing the atmosphere of the ger districts to the center of the city. They hung specially made curtains that usually line the inside of a ger (yurt) into gates, making a public place a “home” for dialogue. They plan on turning their recent installation event in the ger district last week into a more regular occurrence, almost like a public art event, beginning again after the July Naadam holidays.

To the Origin arrived back from their long nomadic journey. They showcased their work, their variation on a ger (yurt), and did a performance that collected the works they showed in the countryside, transposing it back onto the Ulaanbaatar city fabric. “If you can understand this performance, you can probably understand most things about nomadic life,” explained the project leader. They will continue working on the documentation and digital components.

Everything For Sale showed the results of their initial work — selling fresh air, animal bones, and CDs with the sound of “silence” at one of Ulaanbaatar’s most famous black markets — Narantuul. They created print material to promote the “store” and will continue selling their work and talking about different types of pollution with the public. During their black market sale, someone bought a bag of air and sucked it down in one go, which says a lot about the state of air pollution and how the public understand it in Ulaanbaatar.

After the public event we spent several days compiling the artist editions for the hasha surveys, delivering them, and collecting feedback on them from the new Mapping Collective members.

The mapping and workshop materials now belong to the Mapping Collective of Ulaanbaatar — a diverse group of middle-aged ger district residents and 4H volunteers. All equipment will be part of the American Corner makerspace, at the Ulaanbaatar Public Library. The American Corner is a public space inside the Ulaanbaatar Public Library, maintained by the local U.S. Embassy and common in a lot of countries, that provides resources and programming. We held talks at the Ulaanbaatar American Corner, and 4H has been using the American Corner for education and workshops for the past 2 years.

Binderya will lead and coordinate new and continued site surveys as part of the 4H programming in the fall, and I will be supporting her remotely with curriculum ideas. While I can’t be there, I know the project is in good hands, and in many ways I’m surprised and deeply satisfied that it feels like just the beginning of a much bigger project.

After all this work, I was heading home to the U.S. and everyone else was off to Naadam celebration and adventures. But before heading out there was one very important thing that needed to get done: take our amazing volunteers out bowling!