As a daughter of immigrants in Turtle Island (aka North America), I strive to be in allyship to the original peoples and the land and waters that nourish me by activating multisensory storytelling and interdisciplinary art, including sculptural installations, performances, lectures, community engagement, writing, olfactory art and experiential technology collaborations with Native culture bearers, creative technologists and scholars. This trajectory shapes my approach to the American Arts Incubator (AAI) exchange where I will be supporting social inclusion of Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian populations in Otavalo, Ecuador through sharing how new media storytelling may shift dominant narratives.

I will be working with Centro Intercultural Comunitario Yawar Wawki Casa de Artes that is housed in Museo Viviente Otavalango, which previously was a textile factory that exploited Indigenous labor for two centuries until it was taken over by workers in 2011. Within this context, Casa de Artes counteracts marginalization and historization of Indigeneity through revitalizing Kichwa language, music and weaving. I am humbled to work with resilient people that embody self-determination. With my workshop participants, I hope to develop site-specific extended reality content to support spreading the story of self-empowerment. Our process will be a co-inquiry on how new media can amplify voices critical to futurity and challenge the notion that indigeneity and modernity are incompatible.

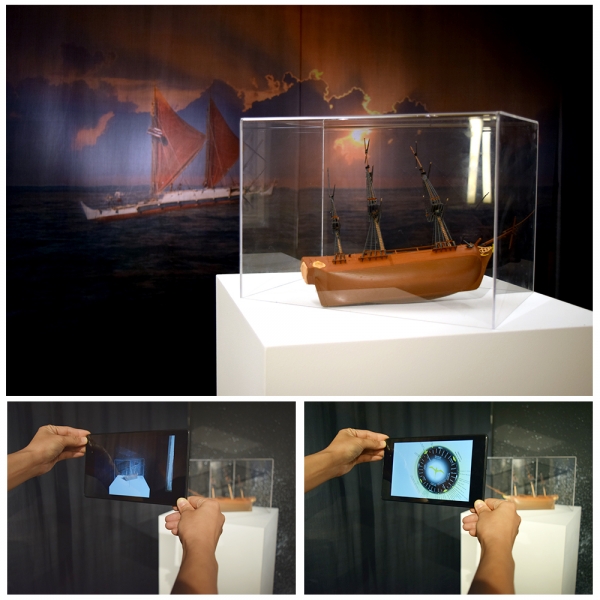

I want to take this opportunity to broaden general conceptions of technology to include ancestral technologies such as weaving, agriculture, plant medicine and wayfinding. I credit my AAI mentor Cristóbal Martínez (read his writing on Tecno-Sovereignty: An Indigenous Theory and Praxis of Media Articulated Through Art, Technology, and Learning) who pointed out that weaving was the first computer and that we must always question the ideologies embedded within the technologies we use, and how they may occlude other forms of literacy and perpetuate power structures. This resonates in an age where we rush to embrace new technological trends without contemplating how often they are derived from military initiatives that were once instrumentalized against certain marginalized communities. Navigating these power dynamics will be one of the first challenges I will face as the Incubator’s lead artist and I hope to find a balance between emerging and traditional media throughout our workshop.

Drone VS. Fort, Rhunhattan Project, April 2017. Image by Beatrice Glow and Highway101, etc. Exploring the embedded ideologies of technology, we used a drone to photograph Fort Belgica that was built by the Dutch East India Company on the original Spice Islands of Indonesia. By using 20th century military-derived technology (drone) to document 17th century military technology (fort), I reinterpret and subvert the ideology belying the drone and use it to support decolonizing perspectives.

Gearing up for the exchange, I have been rereading Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples by Linda Tuhiwai Smith. I am also learning about Andean culture and cosmovision through learning the Kichwa language. For example, the word for “person” is runa, and the full definition is “a being of nature that acts with force and wisdom.” My teacher gave me a Kichwa name that realigned me on the path of runificación, which urges me to act in my full potential while being conscious of my relationship to the ecosystem and the cosmos.

During my stay, I hope to learn more about how Indigenous communities in Ecuador have been at the forefront of environmental stewardship, most recently evidenced by the Yasuni resistance against the pipeline construction in the Amazon Rainforest as well as the 2008 constitutional enshrinement of the values of sumak kawsay (buen vivir)[1], whose vision for environmental health is critical to a sustainable and socially-just future. I am curious to learn how this is implemented on a day-to-day level, the challenges, and how these takeaways may guide and strengthen parallel North American efforts. My time in Otavalo will undoubtedly expand my understanding about the ramifications of colonialism, environmental racism and Indigenous revitalization.