Guest blog post by project photographer, Yen Nguyen.

Over dinner one evening, I talked to my husband and our two sons about an LGBTQ art project I was about to engage in. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) are terms we all are familiar with, even for our boys aged 15 and 11, however we couldn’t work out a definition of “queer.”

More Than Love on the Horizon is the art project originated by Vietnamese American artist Erin O’Brien, who identifies herself as queer. The project aims to increase the visibility of the Vietnamese LGBTQ community through the use of digital media art. Prior to this project, I didn’t even know that the “Q” had become the fifth initial and an integral part of the community.

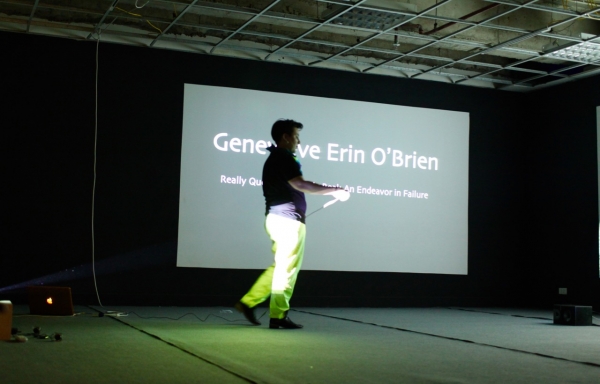

In Erin’s artist talk, the first project activity, she explained her queer identity and what’s Really Queer or Queerly Real about her art, which is mostly performance based and dedicated to enhance social justice for the LGBTQ community. As the project’s other activities unfolded, it was clear that she wanted to experiment using these art practices with members of the LGBTQ community in Ha Noi.

I was amazed by Erin’s energy and ability to engage the young participants in different activities – from a creative workshop, to shooting hologram videos, to proposing their own projects. Her ‘craziness’ is contagious. She managed to get them doing many things, like running around, shouting, laughing, posing, dancing and acting, some of which they are not used to or probably never been exposed to.

Erin needed translation while doing the activities. She admitted she can understand words in Vietnamese as long as they are related to food because of years eating Vietnamese food which, by the way, she can cook, too. She could cook for a family several weeks in a row without repeating any dishes, and apparently, she cooks for her dogs back home in LA. Before coming to Vietnam to work on this project, she filled the freezer with her homemade food; enough for her dog to eat for all the weeks she is away. Erin also expresses her art in the culinary realm by creating her own artisanal sausages with recipes inspired by her family and friends’ stories, under the brand “Meat My Friends.”

Despite her limitation in Vietnamese comprehension, I saw that Erin could understand LGBTQ stories before they were even translated, particularly while we were shooting for the holograms. She laughed, she cheered, and she cried as individuals shared with her their emotional stories. Stories that demonstrated the clear need for Erin’s work, even when there have been remarkable recent achievements in increasing LGBTQ visibility in Vietnam.

After just a few days of working with her on her project, I began to understand Erin’s queerness. I felt comfortable explaining to our sons: “Queer is simply being different, and it is okay to call people queer.”